In the past 10 days, I have:

- Climbed through insect-ridden mangroves once more to take their measurements

- Began working on my environmental DNA project!!!

- Made a funnel cake (sort-of)

- Abruptly halted my environmental DNA project because I did something wrong again

- Turned 21

- Actually used the kitchen for a proper meal

I feel confident in saying that I have become one with the mangroves. This past week, our group has taken above-ground biomass surveys, root density counts, habitat complexity scores, fish surveys, eDNA surveys, and root lengths. That’s all in addition to the past three weeks of processing the mangrove roots themselves in lab for the living organisms on them. All of these measurements help describe the structure and biodiversity of mangroves so that we can compare differences between sites and ecosystems. It’s crazy to think you can quantify so much in such a small sliver of the Caribbean.

In addition to this, I finally started taking data for my project! I am taking water samples from the ocean at all of our marine sites to see how environmental DNA floating in seawater matches up to the whole organisms we can see when processing mangrove and seagrass samples in the lab. More specifically, I am comparing my environmental DNA water samples to traditional fish surveys. While other scientists are swimming through the water, identifying and counting fish, I am sampling the water to capture the DNA that the fish are shedding. This way, we are all capturing a moment in time in mangroves, seagrasses, and coral when fish (and their DNA) are present. It’s a lot easier and less invasive to take water samples than to spend hours snorkeling through these ecosystems, so hopefully I find that the fish diversity in my water samples is similar to the fish diversity that the other scientists are finding. Plus, it will be interesting to see how fish diversity changes between mangroves, seagrasses, and corals.

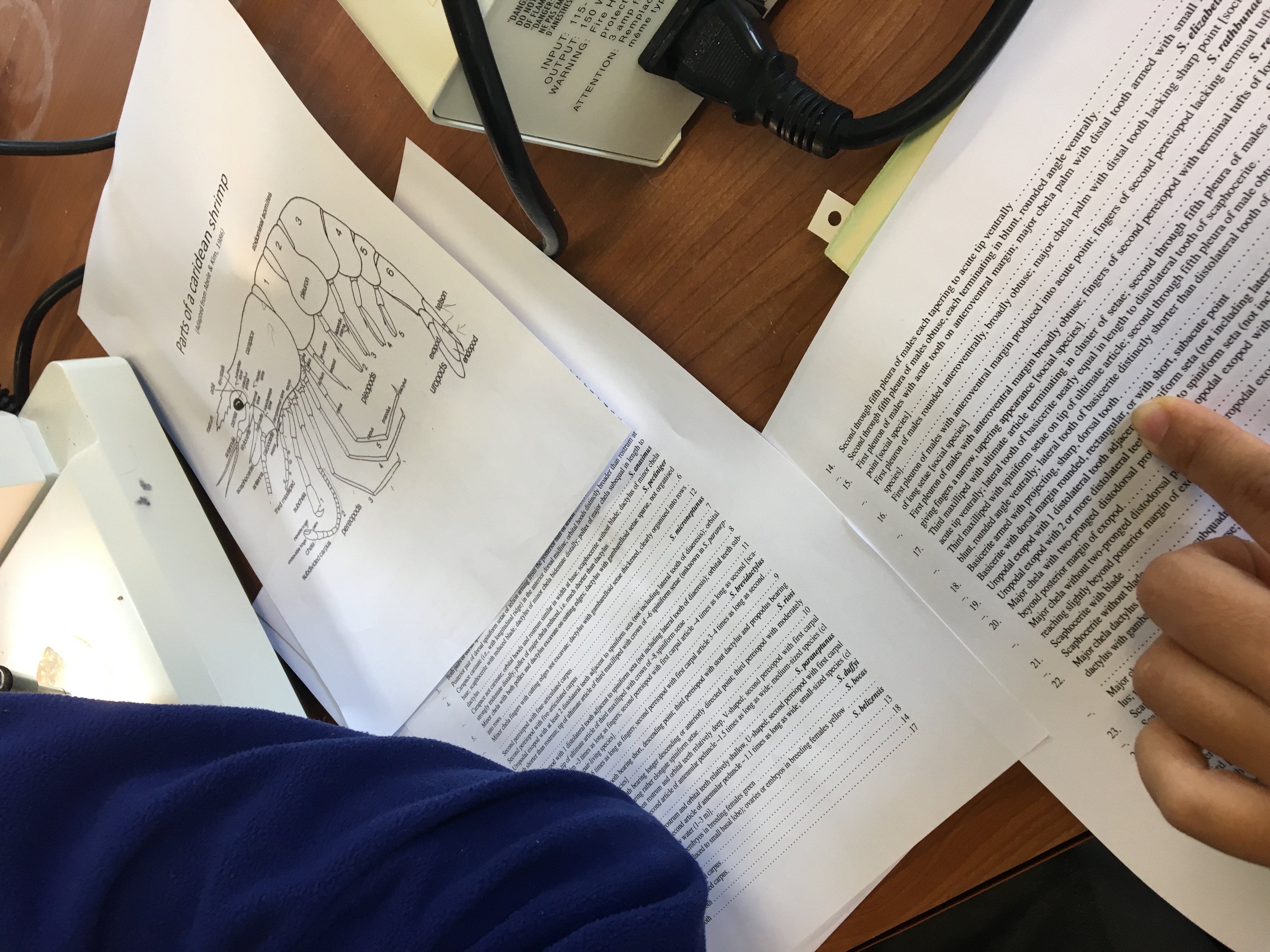

Because it takes much longer to do a traditional fish survey than it does to sample water, I filter my water samples while in the field on the boat. To filter a water sample for its environmental DNA, I push water through a filter that is fine enough to trap DNA in it, but not the rest of the water. That filter gets frozen until DNA extraction can be done. In order to force water through such a small filter, I use a pump connected to a drill. This whole system was optimized with the Funnel Cake, a vision of Coll’s and mine. We found a broken bucket and sawed off the cracked top. With the bottom of the bucket, we connected together all the parts necessary for water filtering. Now, the whole system fits into something close to the size of a baking pan…thus the name Funnel Cake.

The movement of water in the Funnel Cake is from left to right. First, the water sample is pre-filtered on the plastic tupperware with mesh and goes into the funnel (the cup-like thing with the blue bottom). The blue bottom holds the filter that will catch the eDNA. The waste water will go into the Erelynmeyer flask to the far right. Inbetween is a metal and plastic peristaltic pump that forces water through the filter and moves water through the whole system. It’s powered by a cordless rechargable drill I bring onto the boat.

But then… a small disaster struck. I brought replacement filters to put into the funnels (the cup-like thing on the Funnel Cake), but they were the wrong item. Now, sampling has been briefly halted and I will stay behind at the field station a bit longer to finish. Such is the reality of field work – mistakes may happen, but most are easily remedied. A package from Rice will be in my hands soon and my facial expression will be the same as the one below when another package for me arrived (thanks Correa Lab + BioSciences crew!)

Remember that equipment (filter funnels) I forgot at the beginning of my trip? After a long journey, they finally arrived and marked the beginning of my project sampling! International shipping is super tricky.

Oh also, I turned 21 last Saturday! I had been celebrating the long overdue start to my project by eating delicious food and legally having a few happy hour drinks after long days in the field. On my actual birthday, I helped decant sediment samples and then went out to dinner and dancing. I ate the best fish burger I’ve ever had, along with a fresh fruit smoothie with a splash of rum.

After a long day in the field, we rushed to a happy hour and then bought out a small empanada stand. We couldn’t resist eating while walking!

Today, I made pineapple fried rice for the group and an apple birthday cake was made for me by Rosalyn (and others)! Even though a lot has happened this week, it’s nice to know that there is always a supportive group nearby to keep spirits high! 🙂

You know you’re extra when you stuff pineapple fried rice into a martini glass to shape it and add a pineapple leaf garnish on top.